Many managers struggle to give constructive feedback to their direct reports – a recent survey found that 37% are worried about a potentially negative reaction.

But a wider problem emerged from the same survey, which found that the vast majority of bosses (69%) are uncomfortable communicating with their employees in more general terms – from giving clear directions to holding 1-2-1s.[i] Unfortunately, tough conversations are a fact of business life, and while avoidance is a good strategy when, on reflection, you decide the problem at hand isn’t really so much of an issue after all, there will undoubtedly be times when tackling behaviour is necessary.

Drawing on our workbook Preparing for a tough conversation, we look at five ways you can approach that difficult chat.

AVOID THE FUNDAMENTAL ATTRIBUTION ERROR

“You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

Two employees both miss a business critical deadline. One person’s costly mistake is attributed to a bulging to-do list or a family emergency, the other to what you perceive to be his or her current lack of motivation and reliability issues – they shouldn’t be trusted with such important assignments in future. The latter is an example of the Fundamental Attribution Error at play, whereby we attribute people’s behaviour to their core character rather than to their situation. In a work sense, it’s much easier to look at ourselves and the colleagues with whom we have the best relationships one way, and other associates in different terms.

In order to enter into a problem-solving mindset, you must first ensure that you’re not bringing any pre-existing biases to the table. This is not about making excuses for bad behaviour or letting someone off the hook; it’s simply about taking the time to understand the bigger picture and what might be going on for the other person. Avoid oversimplifying the problem; after all, if it were simple, it probably wouldn’t be causing you an issue in the first place. Try to remove emotion, set aside any filters through which you might be viewing the situation, and examine it as an objective observer might (if you struggle with this exercise, draw on the opinion of a bystander and do some role-playing).

Even if you ultimately decide that the reason for the deadline failure was poor reliability, by examining the subject from various other angles, you might have just uncovered your direct report’s likely defence, and can therefore prepare accordingly.

THE ZIGZAG MODEL

“I have six honest serving men. They taught me all I knew. I call them What and Where and When and How and Why and Who.”

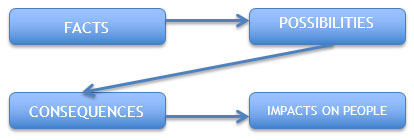

If you’ve ever done any kind of personality testing like Myers Briggs, you’ll be aware of the differences between ‘thinkers’ (objective, firm, rule-driven, detached, clear and analytical) and ‘feelers’ (subjective, tender, appreciative, involved, sensitive). Neither is right or wrong, they are merely preferences; however where a tough conversation is concerned, it’s best if you can incorporate elements of both types, so that you’re truly seeing the whole picture.

This is where the Zigzag model can help:

“Start by considering the facts, details, and what has happened to this point. Only then move onto the bigger picture and consider how the issues may link to other areas or problems. What are the future considerations? Think through what the consequences might be. Look at cause and effect. Examine reality, logical analysis and a rational point of view. Often we stop here if we are a Thinker. However, it is essential to also consider the emotional impacts and what is best for all the people involved, not just business priorities.”

FOCUS ON DESIRED FUTURE BEHAVIOUR

One of the biggest concerns of the manager delivering feedback is that the individual will respond defensively or otherwise negatively. It’s much harder for your employee to do this if you frame the feedback around wanting to offer a valuable lesson in order for the individual to grow or progress. Ask yourself whether this is indeed your objective, and if you discover that you’ve a different, less directional or positive reason for wanting to have the conversation, question whether you’re taking the right approach.

A negative reaction is also far less likely if you keep the conversation two-way. Demonstrate that you want to understand more about what went wrong from the other person’s perspective and challenge them to uncover solutions to stop the problem arising in future. The aim is to establish – by mutual agreement – what behaviour or actions you want to see less of in the future and what you want to see more of. By working together as a team you’re more likely to get buy-in from an employee than if you simply hand them a “teach sheet” of dos and don’ts.

More advice for line managers on the everywomanNetwork

Delivering feedback: 3 ways for new line managers

Recruitment dilemmas: how do I uncover a candidate’s authentic self?

New ways to think about delegation

Career surgery special: dealing with difficult colleagues

The six people you’ll meet in a new job – and how to deal with them

Personality clashes: 5 techniques for dealing with conflict at work

[i] Survey by Interact: February 2015