If you have leadership in your career sights then it’s never too early to start preparing. Setting yourself up for the transition and building on your leadership credentials is an important investment for the future, even if you are in a junior or mid-managerial role right now. Group Captain Janet Hamilton-Wilks reveals why in your early roles you need to embed self-awareness, a spirit of boldness and authenticity — and what a military career can teach everyone about preparing to lead.

- Leadership is not just a ‘work’ thing… As an officer in the military, leadership is there right from the start, so in a sense there is no ‘transition’ to it. I did six months of officer training with leadership ingrained in it and leadership is built into your early roles. I knew that that was what lay ahead when I was still at university, so although I was doing things I enjoyed back then, if there was a leadership position to take on I would have a go. Anything that starts to help you to understand yourself and how you respond when things get difficult and enables you to learn to adapt and dig a bit deeper, is helpful — and importantly those experiences can come from all parts of life. For me, leadership comes from learning to lead yourself through tricky situations and make good decisions — because ultimately that’s how you will lead others.

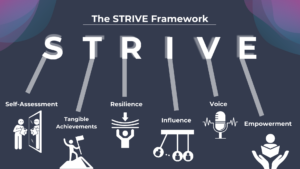

- Self-awareness is key to developing good leadership, and that starts early. You can only be the leader that you are. So, while it’s helpful to read about other leaders and get a sense of how they’ve taken things on, ultimately how you distil that into your experiences and the challenges you will face as a leader is up to you. Self-awareness is vital to you being able to lead in a way that is authentic for you. You don’t want to be putting on a mask each day, because you are going to have to sustain leadership over years and years — and that’s going to be exhausting if you’re doing something that’s not coming naturally.

- Continuously seek out feedback… It’s important to get information on your style and how it impacts those around you by asking for feedback from peers, bosses and stakeholders, and then — most importantly — accepting it. Sometimes that feedback will sting, and you have to find a way to see the good bits in it — understanding what you’re strong at and what people want you to keep doing, but to also accept the bits that make you think, ‘I hadn’t realised that’s how I landed with people’. There’s something about finding your way through that and challenging yourself to try things differently that builds character and will ultimately help build you as a leader.

- Don’t wait for permission… There were times early on in my career when I could have been bolder about my leadership — I think perhaps I was waiting for permission to do things. It took a little while for me to realise that if I thought something was important and valuable then there would be others who probably did too — and that I could start to instigate and organise things, sometimes going further than my role specification. When that leadership transition comes, don’t be too self-limiting with it — be bold, do something that stretches you. Find the people who have similar values or interests to you and work together and you’ll do something you might never have thought you would do. You can start to embed that approach now in your career, wherever you are in it.

- Push yourself out of your comfort zone from the start… When you join the military, you do lots of jobs early on in your career, and you don’t always get a choice as to what they are. Sometimes you’re in a location you didn’t expect to be in or doing a role that you hadn’t imagined you would be doing — and you learn that you can adapt and get on and do it. I was never able to just sit still in my career and say, ‘Well, I’m here now for the next five years to do this particular job’. So, in a sense, the military encouraged me to take on responsibility early — it assessed that I was ready and that built my confidence. Then what I found was that my portfolio of experience, contacts and knowledge expanded, and I started to create a reputation and momentum.

- Build your advisory board… If I were speaking to my younger self, I would tell her to get a mentor earlier in her career. I had some good bosses who filled that role, but there’s a military adage that ‘no plan survives contact with the enemy’. There’s something about making that conscious decision and taking that action to get a mentor that forces you to think about what you’re trying to do with your career. You have to think who you want to approach — and why. What do you want from that relationship? And what are you going to offer that relationship? And even though your career plan at that stage may never quite come out in the way you imagine — it probably won’t actually ‘survive contact’ — that thinking and planning is a really important development, especially as part of leadership is about taking a broader view, not just dealing with what is right in front of you.

- Don’t be afraid to stand out… When I was waiting to do RAF officer training, a colleague gave me his advice which was to ‘be grey’ and try to fit in. It struck me as bad advice. I thought it was more important to find out if this organisation was one that worked for me early on, rather than try and fit in and then later realise that it wasn’t quite right. It goes back to the point of being yourself to be able to lead fully. Instead of following my colleague’s advice, I allowed myself to be authentic and at the end of that training, I was awarded the Sword of Honour, which is given to a cadet who has demonstrated outstanding ability and leadership. I wouldn’t have achieved that if I’d gone in and tried to make myself invisible.